about

Blog: Globals

11/26/2024

Blog: Globals

scopes and dependencies

About

click to toggle Site Explorer

Initial Thoughts:

Problems with Global Sharing:

- Access to a datum from widely separated parts of a program's code makes it difficult to understand its use and evaluate correctness of the code's operations.

- If the data isn't wrapped in a class or struct it isn't possible to control or monitor access to the data's values.

- Access to a specific data item in many parts of the code bind all of those regions to the definition of the data. So any changes of that definition will affect all of the clients of the data and may require massive editing and recompilation when changes happen. Thus, the code becomes brittle and easily broken by change.

- All accesses to a specific datum by multiple threads must be synchronized with locks to avoid race conditions in the program's behavior. If the data type is thread safe, like a well designed blocking queue, that may not be an issue, but for primitive and non-thread safe types, global access makes threading models very complex, difficult to reason about, and very hard to make correct.

-

A global datum may be used by two developers working on code for the same process in different and conflicting ways, one interrupting the data storage activities

of the other.

If there are multiple writers and readers of a global datum one writer's value may be overwritten by another writer before being read. This may or may not result in problematic behavior, but if it does it will often be very difficult to find and rectify.

These problems make development, testing, and maintenance of code containing global sharing difficult and often quite unproductive.

Scopes:

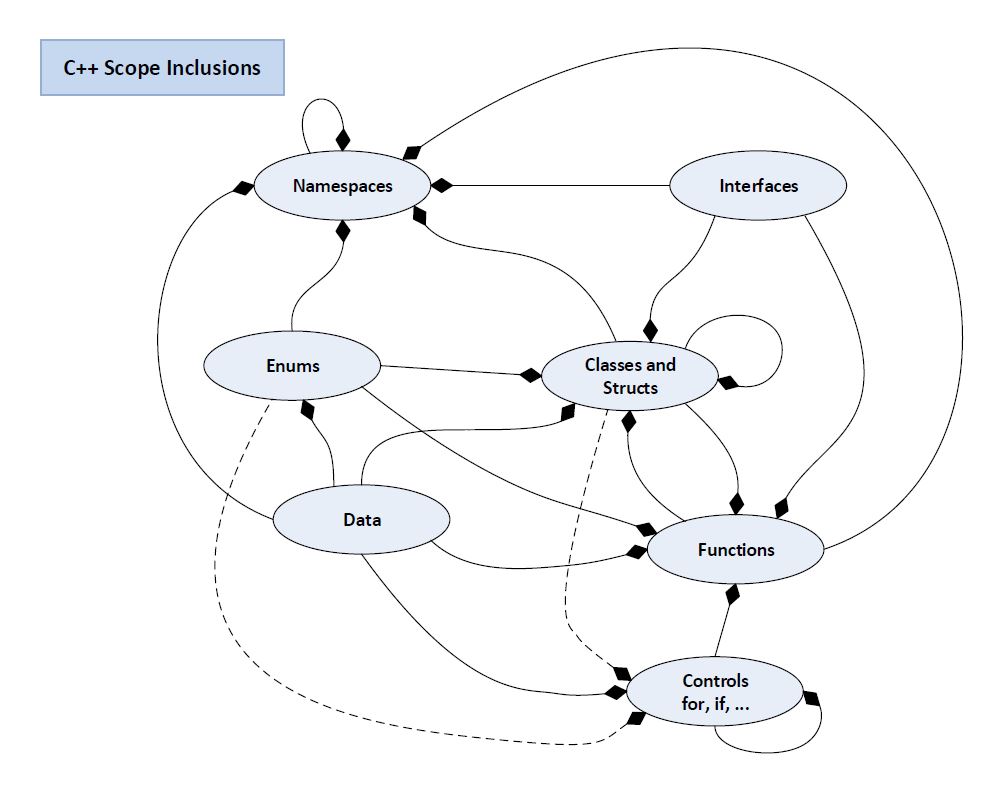

For purposes of this discussion we will define a package as a single source code file in C# and Java, and, for C and C++, a pair of source code files - header and matching implementation. Access to data in the four major development languages C, C++, Java, and C#, depends on scope. These languages define, for each package, a tree of nested scopes using the symbols "{" and "}". Code that resides outside any "{", "}" block is said to be in the program's global scope. There are two kinds of scope: - Namespace, class, struct, and enum scopes are compile-time artifacts. They are syntatical constructs that serve to associate function and type declarations and access specifiers with a class or struct and associate named constants with an enum. They play no role at run-time.

- Function and control scopes have affects at both compile-time and run-time. As the thread of execution enters one of these scopes memory is allocated on the program's stack to hold its calling parameters, local data, and return values. This memory is allocated to a specific scope only for execution and is de-allocated when execution leaves that scope, to be reused for subsequent scope activations. We call this memory a stack frame and normally think of it as lying at the end of a sequence of adjacent frames belonging to its parent scopes, in activation order.

In C# and Java, handles to reference types and instances of value types may be declared only as members of a class or struct or locally in a member function. C and C++ allow type instances to be declared in global scope, in a namespace scope, and as members of a class or struct or locally in a global or member function. Data Access:

Access to data is controlled by the scope in which it resides: -

Global and Namespace Scope:

C and C++ support access by any code in a compilation unit to data defined in the global scope and in namespace scopes. Access beyond the data's compilation unit will depend on declarations in a header file and the use of the keyword static in the data declaration. C# and Java do not support placing data declarations in global or namespace scopes. -

Class and Struct Scope:

Private member data is accessible only to code in member functions, but is accessible everywhere in that code. Protected member data allows access by all code defined in derived classes as well, and public member data is accessible to any code below the declaration of an instance of the class in its scope as well as all the member code in the class and its derivations. Non-static member data is unique to each instance of the class. -

Static Member Data:

The values of static member data of a class or struct are shared by all instances of that type.

What do we mean by Global Sharing?

It's relative. Data defined outside any class, struct, or global function, is global to the program. Non-static member data is global to the instance of its class or struct. Static member data is global to the set of all instances of its type. Data defined inside the scope of a function is global to all code in the function after the point of its declaration. I expect that most developers and language enthusiasts mean program global access when they use the term "global". Note that a database provides program global sharing of data. Its use is subject to some of the same problems as raw data, although most database facilities provide safe multi-threaded operation. So What?

The difficulties we encounter with shared data depends largely on its scope of definition. Data defined in a program's global scope is the most likely to cause difficulties in development and maintenance, as cited in "Problems with Global Sharing", above. As the scope of access is reduced the problems become easier to manage; and for local and non-static member data, in small functions and classes, almost non-existent because the entire scope is designed and implemented by one person at one time in a page or two of code. Constant data defined in the global scope causes no problems and has semantic value, providing a program-wide name for an invariant. Global data with a single writer has only one specific problem - a value intended for one reader may be overwritten with a value for another reader before the first is read. Using global data with multiple writers and readers should almost always be avoided because its just too hard to understand and manage. Java and C# prohibit all use of global data, even the beneficial use of global invariants. Sharing through static member data can be very useful. Here's an example. We've decided to communicate between two processes in our application using enqueued messages. There may be several parts of the sending process's code that need to create and post messages. If they are in different scopes how do they all access the queue? It would be hard to make a simple elegant design that passed references to the queue into every scope that needs access. If we write a small wrapper class that holds a static instance of the queue and makes it available, the code in any other scope that needs access can simply declare an instance of the wrapper class to get to the queue. If the queue is thread-safe, then the wrapper becomes very easy to use. In C++ we can declare the wrapper as a template type that takes an integral type as a template parameter. That will create seperate types for each value of the parameter and so we can define queues that are shared by different categories of users, e.g., those that need acess to an input queue and those that need access to an output queue. Summary:

Use program global data only for program invariants, e.g., initialized once and read many times. Use static member data to share between instances and provide access to a facility, like a queue, across program scopes. But, be aware of threading issues with static member data. While virtually all programs beyond the "Hello" variety need shared data, we should attempt to minimize and localize its use as much as possible.

Next Prev Pages Sections About Keys